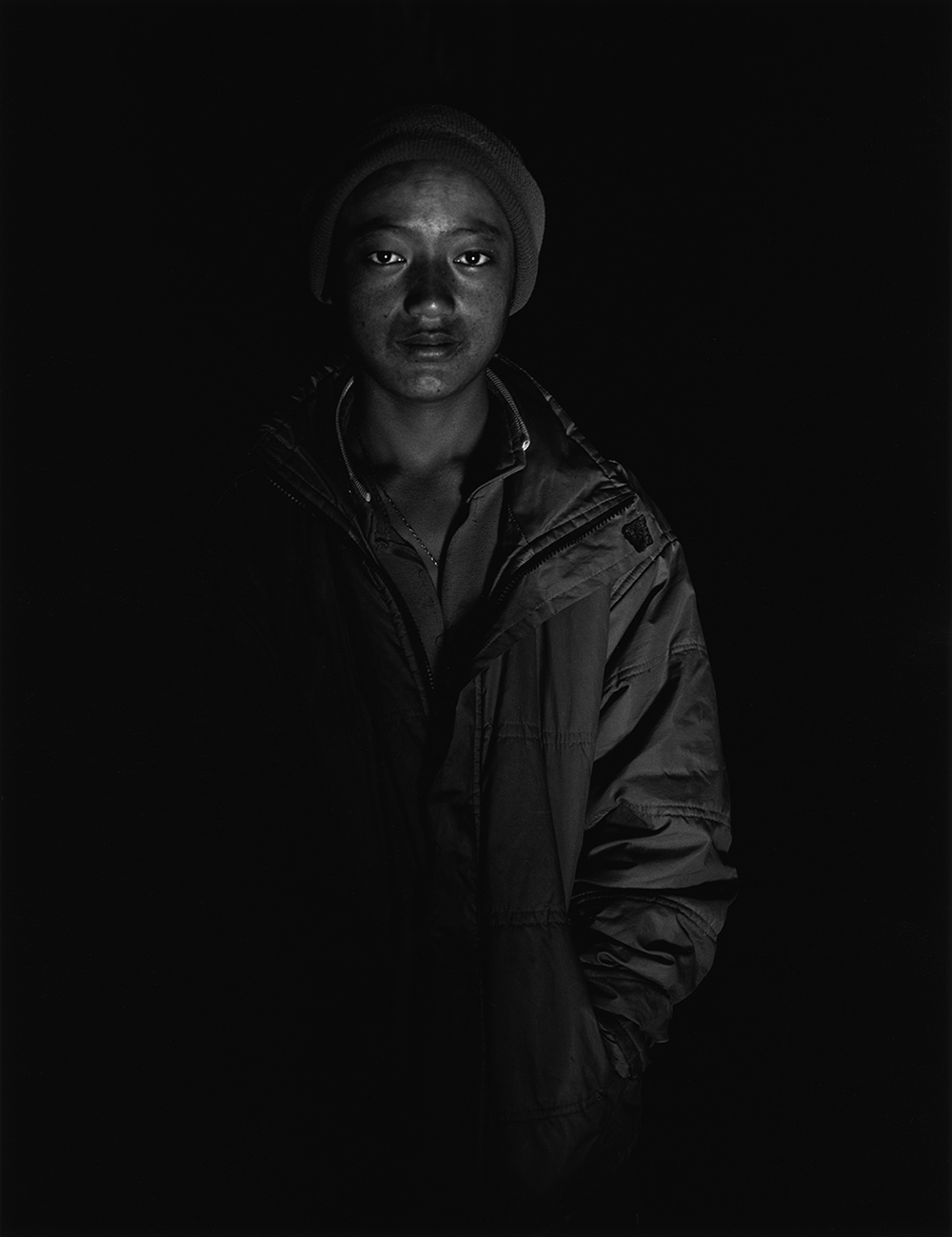

Patriarch of the Calle 8, Yagüita del Pastor, Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, Dario Benjamin Ventura Ventura, took me under his wing 20 years ago when I began documenting the neighborhood where he lives.

Initially, I was unsure if his references to himself as a “León, Toro” and, incongruously, a “Camarón de agua sucia” (lion, bull, and shrimp of dirty waters*) were simply bluster, but after his son came to blows with another man from the neighborhood - who then, together with an assemblage of friends, followed up by pounding on Dario’s door to settle the score - I saw Dario in action. Armed with a dagger, he stood slightly back from the door and dared anyone to cross his threshold. Despite the high emotion of the group of men and the discrepancy in numbers and age (the five or so men were probably in their 30’s, while Dario must have been in his 60’s), not a single soul chose to take him up on his challenge.

On another occasion, I saw a different side of Dario. A young man, devastated by the rejection of a woman whom he madly loved, dove off the top of a steep ravine, half falling, half sliding to the bottom - where Dario lived. Hearing the commotion behind his ranchito, Dario came charging out his backdoor, his single eye assessing the situation. Once he understood what had occurred, his face lit up with jeering laughter and he proceeded to clap and cheer as the “Ridiculo” wiped blood from his face and wobbled in an effort to stand up. (The man turned out to have suffered no serious injuries).

Respected in his home and adapted to barrio life, Dario nonetheless never seemed quite so much in his element as when we traveled to his campo together. He walked through his plots of land, inspecting crops that had persevered even without attention from his “sinverguenza” (shameless) city-dwelling sons, and casually pulled tremendous roots of yuca out of the ground or climbed trees to gather avocados. Naked, smiling, in a natural pool formed at the base of a small waterfall in the river, he swam, and told me of the woman he met decades earlier in this same place… whom he ultimately married.

While others, young and old, have died with alarming frequency in La Yagüita, Dario has lived on, first watching both his children grow to become adults then his grandchildren reach maturity. He has always welcomed me into his community, and even now that "El León" is an octogenarian, were I ever to find myself in trouble in La Yagüita, I would seek him out.

* This turned out to be a reference to his ability to live anywhere.