The Amazon River, as you surely know, is legendary. It’s name alone conjures images of remote jungle and tribal people with little connection to modernity. While there may be areas along its banks that fulfill such legend, much of the river serves as a major roadway, shared by, among others; small boats carrying villagers short distances, indigenous people fishing in canoes, huge barges bringing industrial supplies to cities*, luxury boats housing tourists on all inclusive nature expeditions, military patrols, and multilevel ferries transporting hundreds of passengers on grueling journeys that sometimes last for weeks.

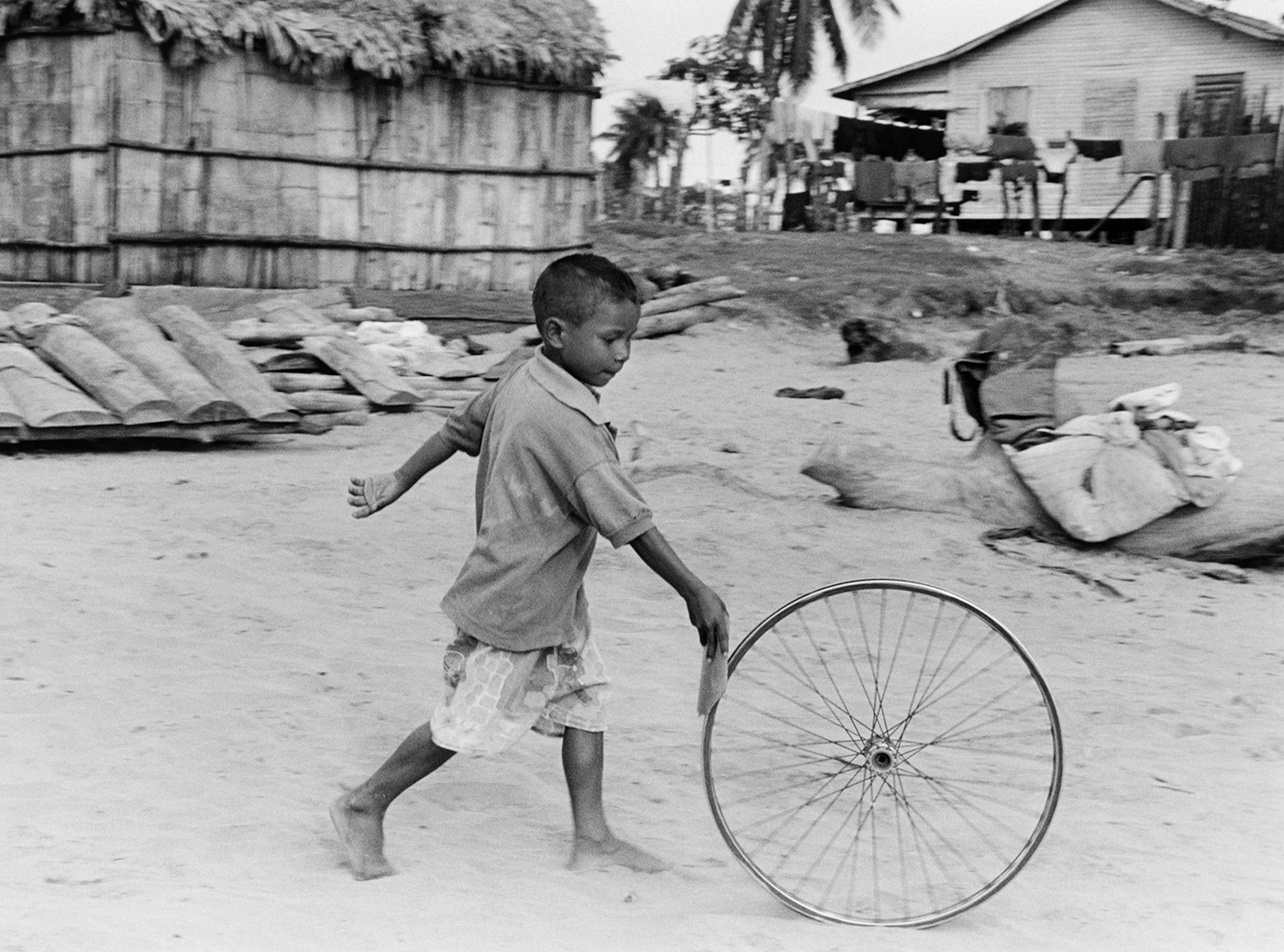

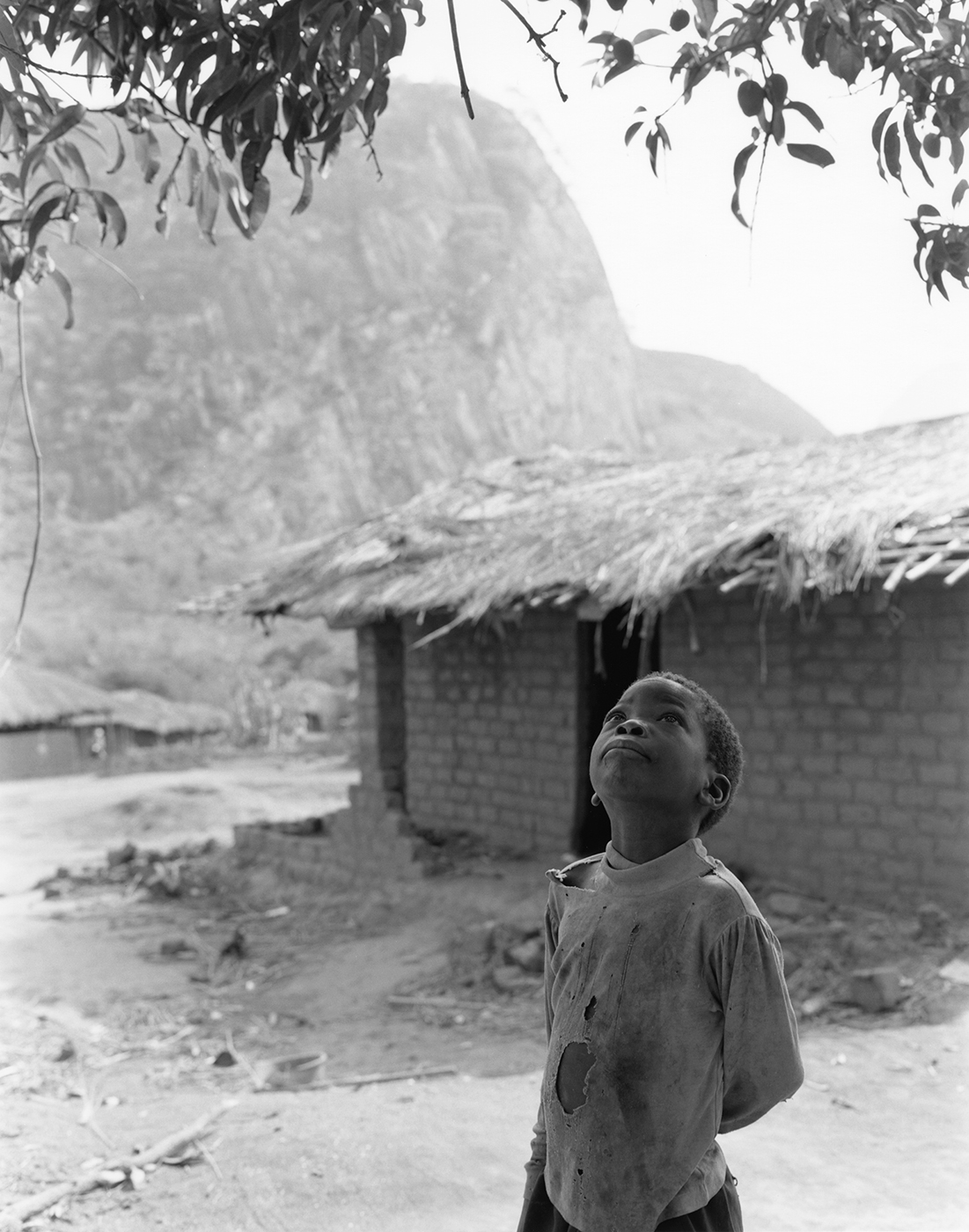

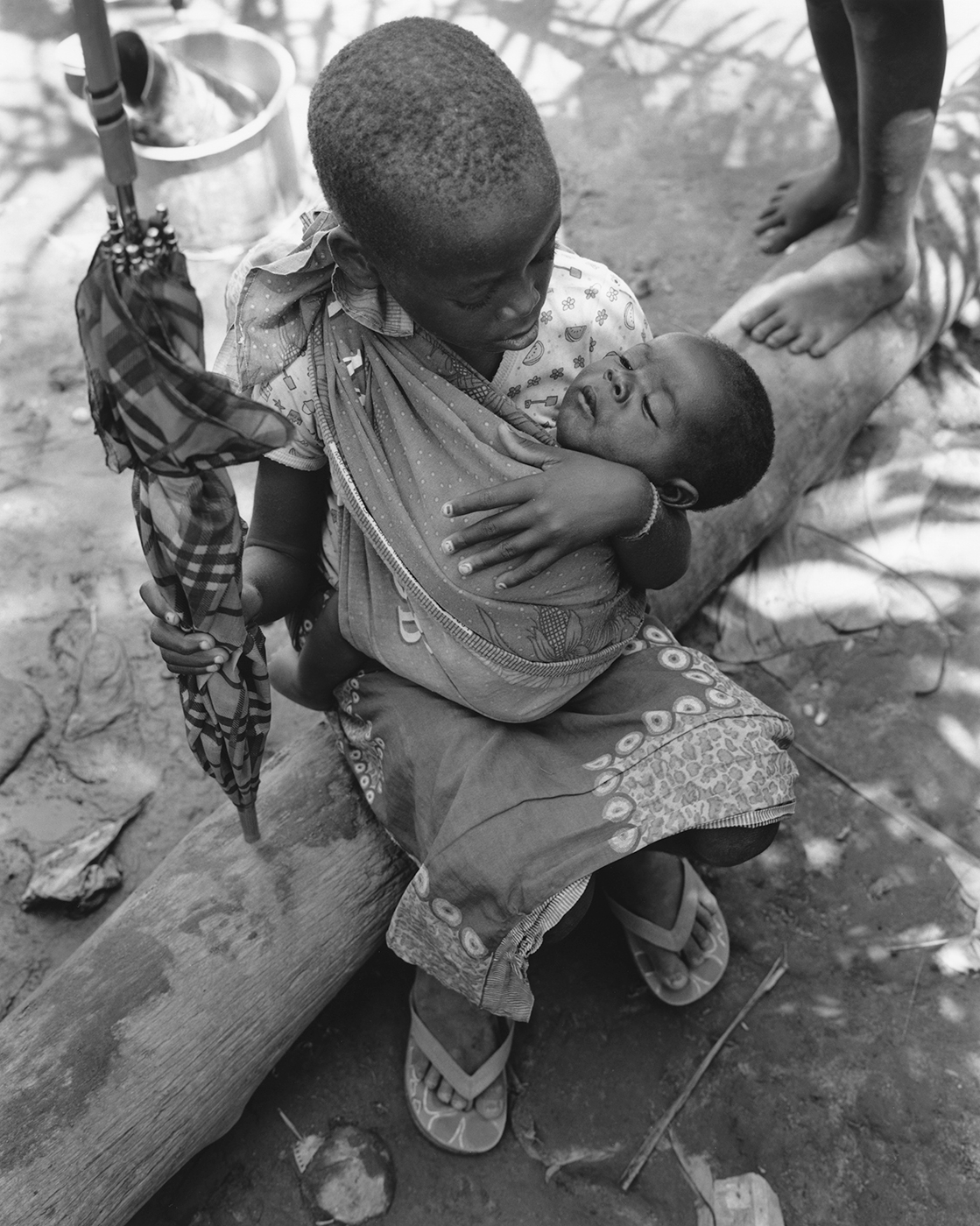

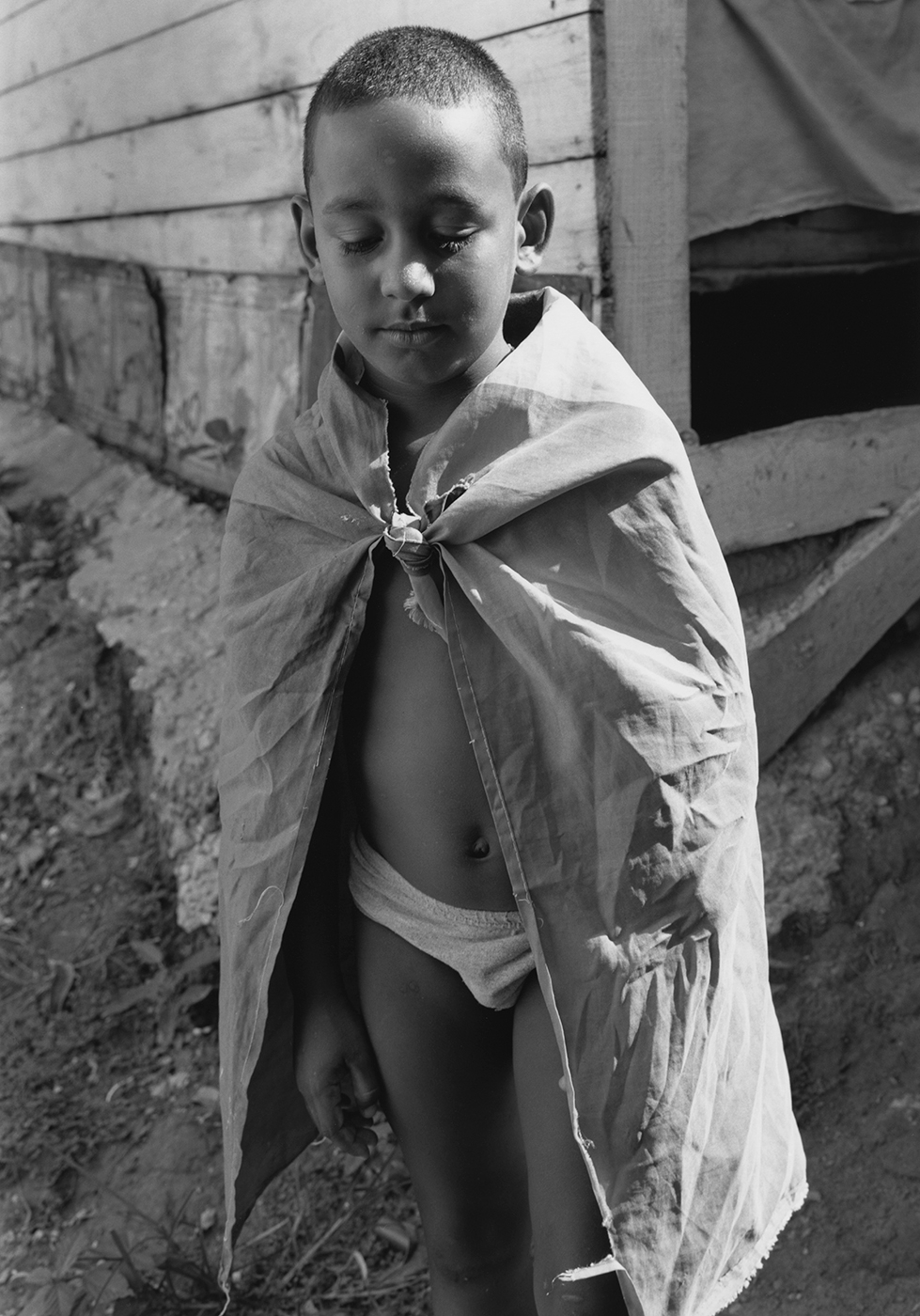

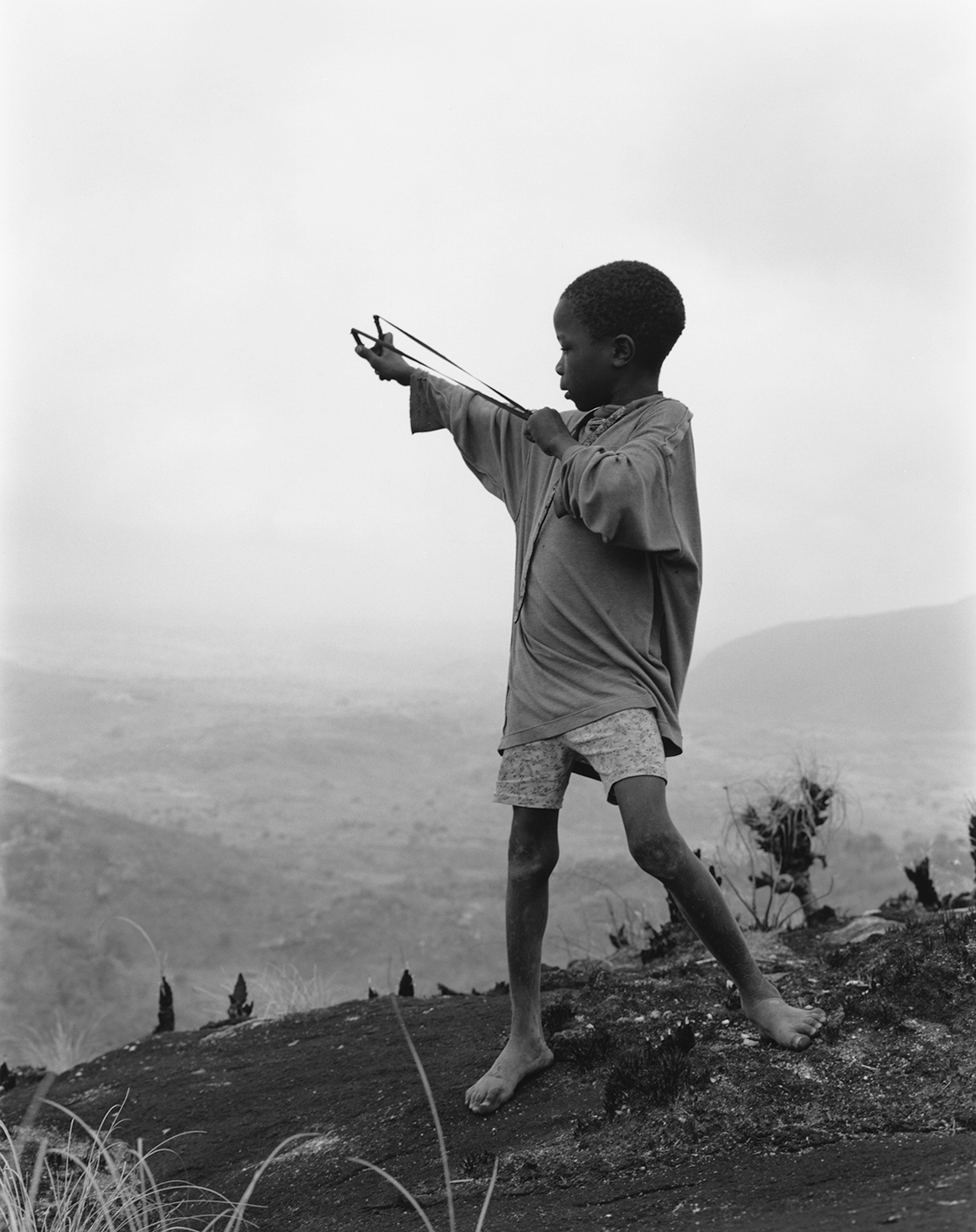

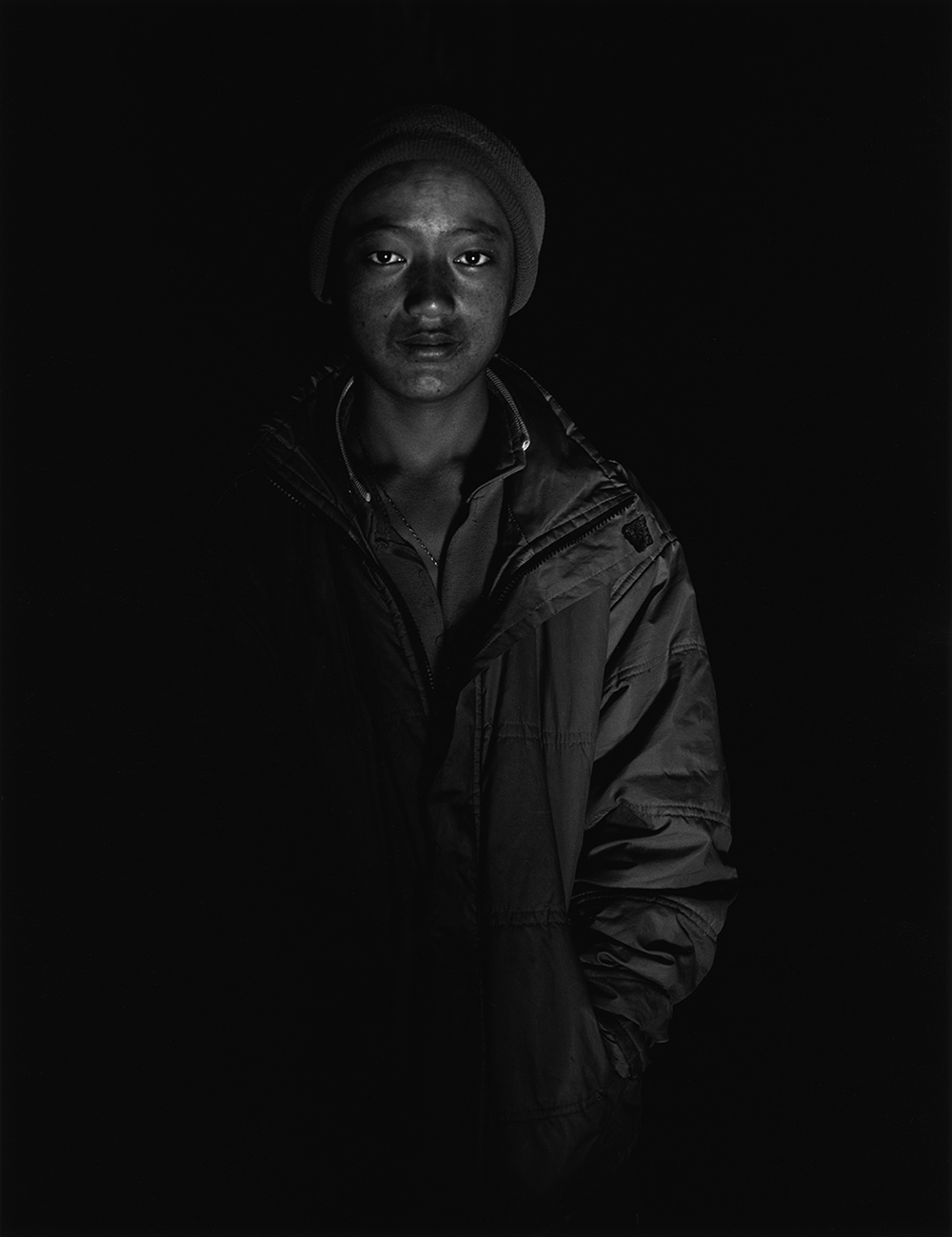

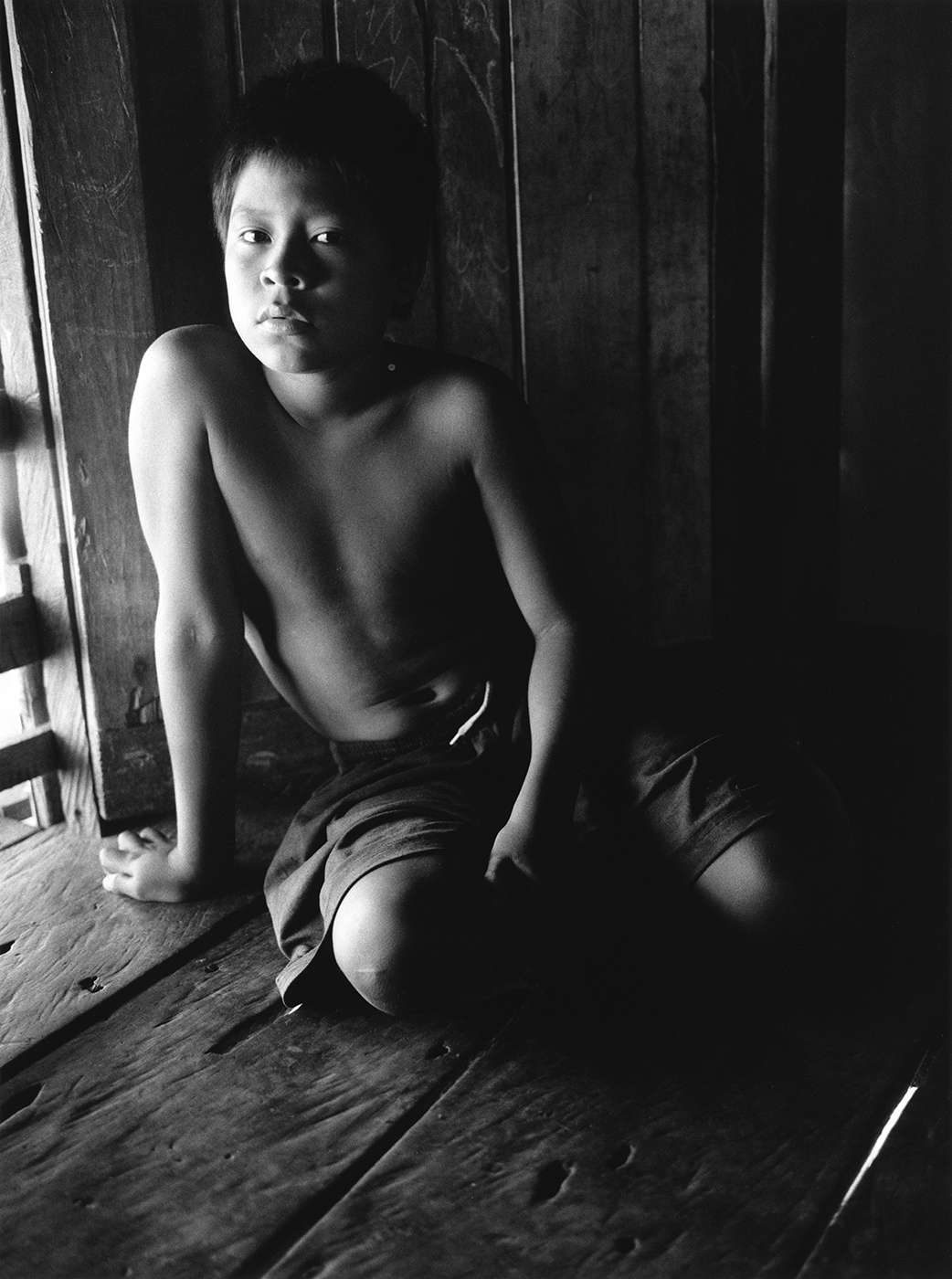

Unsurprisingly, carved out of the landscape in proximity to this “highway”, are communities of varying sizes and character. The three photographs I am sharing are an attempt to articulate the grit and feel of some of the mid-sized towns or cities. Without the glamour of an opera house or baroque architecture like the cities of Manaus or Belem, or the “exotic” feel of barely noticeable indigenous settlements where the few dozen inhabitants subsist on both potato chips and freshly caught fish, the areas I am depicting are without immediate beauty or intrigue.

Nonetheless, they are the backdrop for the lives of many, and as I explored I came to love the ramshackle-nature of the communities and the unusualness of the cast of characters and their dispirit activities. During my explorations through markets, museums, and along public transportation routes, I got a sense of the area’s diversity. I encountered an unexpected addition to a fish market when I noticed a dead monkey for sale - brought by canoe from further upriver - whose luminous white skin was being exposed as an indigenous man carefully used his machete to scrape off the fur. There were people dressed as they imagined ancient Israelies dressed, with robes and rope belts, following a popular religion. A white man sitting in an internet café appeared to be painted from head to foot with a black substance (extracted from a nut), in a manner consistent with traditional indigenous “tattooing’ - having apparently returned from a destination quite remote. There were whispers of drugs and soldiers were stationed to guard the compound of a busted kingpin. Indigenous people, far from their childhood communities, were sprawled in drug or alcohol induced catatonia at the ports. Other indigenous people were living happily with their families and neighbors in houses built on stilts - enjoying electricity, access to medical care, food, and kinship. Tourists and the town’s elite mixed in air conditioned cafés as they sipped cappuccinos and ate freshly baked pastries.

Depending on one’s perspective areas like the ones shown might be apocalyptic or flush with opportunity and riches… but for a traveling photographer, they were nothing short of unique.